From 2016 report:

Natural sources of arsenic in the Cook Inlet Basin include volcanic ash, glaciation, and mineral deposits. Only a minimal contribution of arsenic results from human activities like wood preservation (Glass and Frenzel, 2001). Arsenic is naturally present as a compound in rocks within the Kenai River Watershed, and as a dissolved metal, it can be acutely or chronically toxic to fish (Glass, 1999). The Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (ADEC) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) have set the standard at 150 micrograms per liter (µg/L) for freshwater aquatic life chronically exposed to arsenic and 10 micrograms per liter (µg/L) for drinking water (Appendix X) (USEPA, 2014; ADEC, 2008).

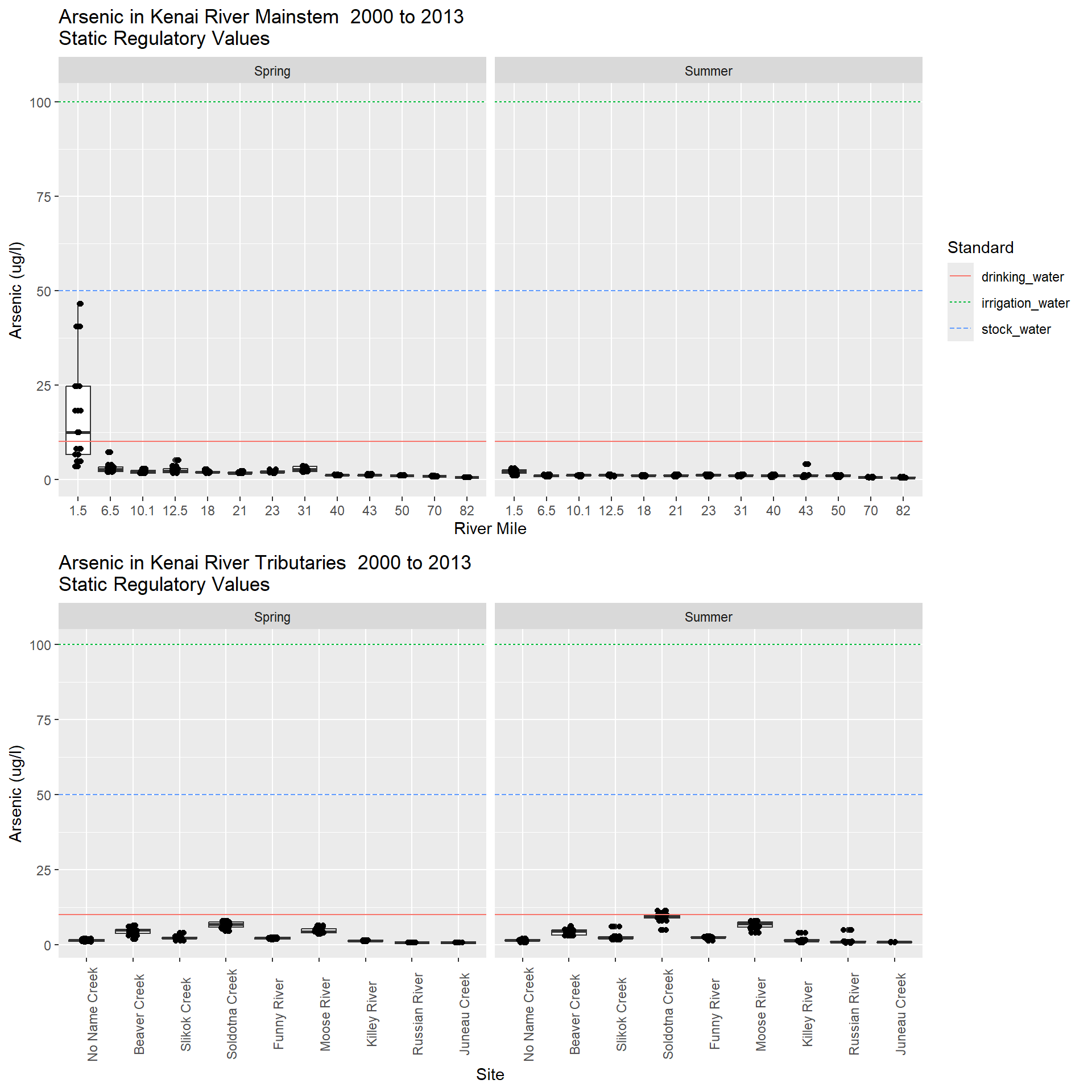

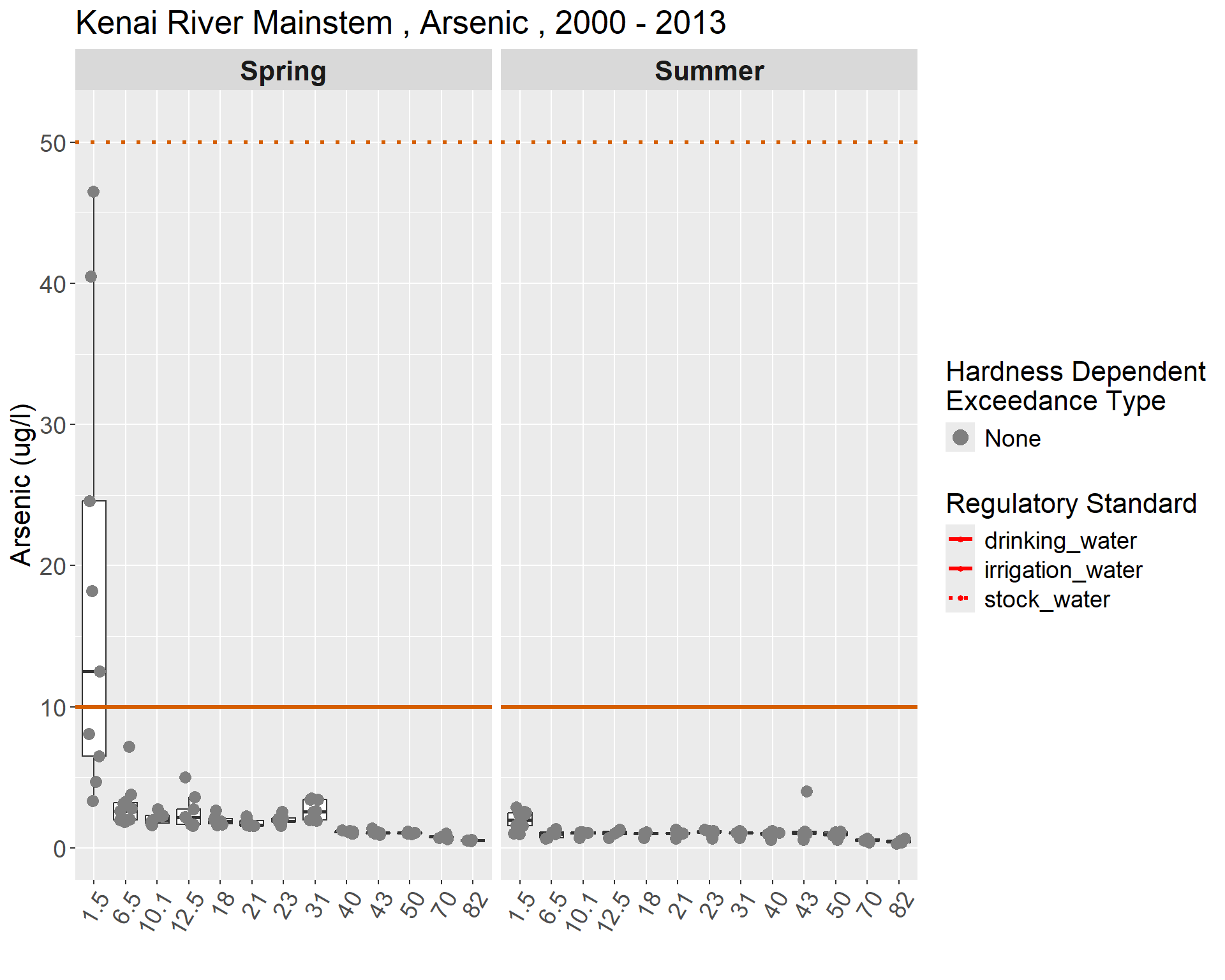

None of the samples exceeded the Alaska or federal standard for freshwater aquatic life at any sampling location in spring or summer. The highest level detected in the mainstem was 46.5 µg/L at Mile 1.5 in May 2007, and arsenic was not detected on many occasions below the method detection limit (MDL) of 0.25 µg/L (Table 6). In the Kenai River mainstem, Mile 1.5 had the highest median level in the spring event and summer monitoring event, followed by Mile 6.5 in the spring event and Mile 23 during the summer monitoring event (figures X & X). In the mainstem, higher arsenic levels occurred in the spring samples, while the tributaries levels were higher during the summer with more detected levels between the years 2007-2014 than any of the previous years. (Tables X & X)

The highest concentration on the mainstem occurred at Mile 1.5 where arsenic was detected on every sampling event after 2005, while arsenic was detected on all sampling dates at Beaver Creek, Soldotna Creek, and Moose River. The concentrations of arsenic ranged from a high of 12.8 µg/L in Soldotna Creek in summer 2014 to below the MDL of 0.25 µg/L in many locations. Of the tributaries, Soldotna Creek had the highest median level, followed by Moose River and then Beaver Creek in summer and Soldotna, Beaver and Moose in spring. No Name Creek had the fewest incidences of arsenic detection of all the tributaries. (Tables X & X)

When comparing the arsenic levels to the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation standards for drinking water, the main stem at Mile 1.5 is the only station that presents multiple exceedances. All exceedances took place during the spring sampling events. (Tables X & X)

Concentrations of arsenic are generally lower in surface streams than in groundwater, which is typically the source of drinking water (Glass and Frenzel, 2001). The USEPA set the criterion for arsenic in drinking water at 10 µg/L because arsenic has been linked to cancer, skin damage, and circulatory problems (USEPA, 2003). Although the levels of arsenic reported in this study do not exceed the national criterion for the health of an aquatic community in freshwater, groundwater may contain concentrations that are hazardous to human health, and all sources of drinking water should be tested for arsenic.